Emerald Shores just launched on PS Vita this week, and with that, I thought I'd write up a quick devblog of what went into making the game playable in terms of optimization.

Disclaimer

Everything described is

very specific to my own experiences with my development environment, particularly the engine the final game ended up being built in (GameMaker: Studio 1.4). If I say "X was slow on the Vita", that doesn't mean the Vita itself is at fault for the slowness at all - many [obviously much more demanding] games run perfectly fine on the Vita. Rather, these are areas that needed optimization when using this specific engine in the ways that I was specifically using it.

The need for optimization

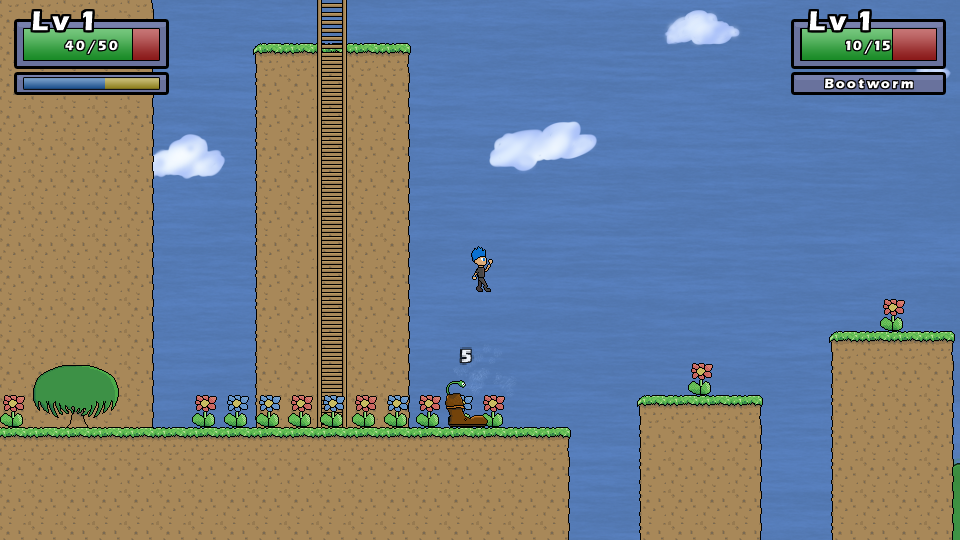

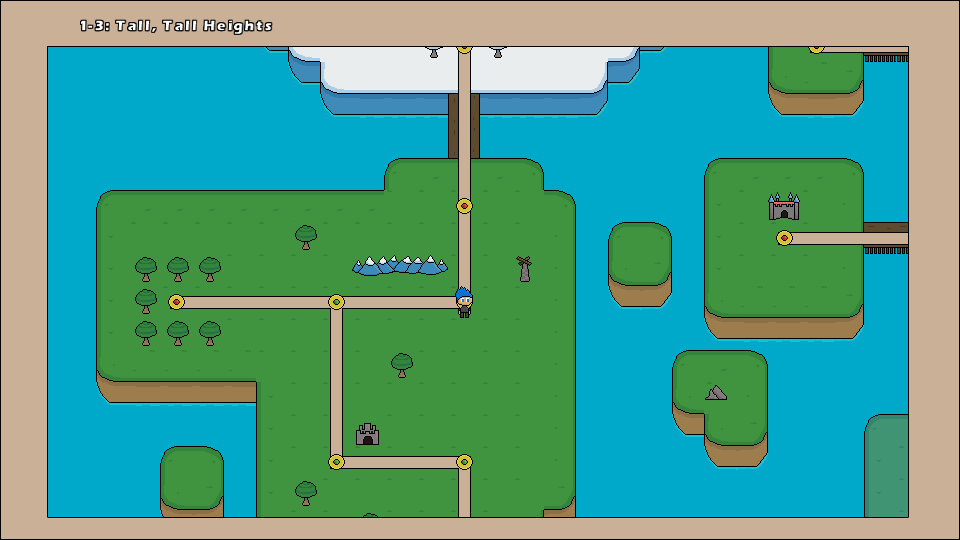

Although the game ran fine on PlayStation 4 and modern PCs -- with a smooth 60 FPS framerate throughout and virtually instant loading times-- the PS Vita version needed a lot of love in both of those areas.

It was a surprise to me that this was an issue, because the game is a fairly simple 2D game on a technical level, and because the previous engines the game was being built in ran it fine: C#/PlayStation Mobile initially, and then the C++-based PhyreEngine.

In the end, optimizing the game for the Vita alone ended up taking a fair chunk of the game's overall development time. While the game in its final state still has a few hiccups, it's at least very playable, when initially the load times and framerate would have been unbearable.

Loading time optimization

Prior to optimization, levels took a long time to load. Larger levels took 20+ seconds to load, and each time your character died, you'd have to wait the entire time again.

Partial reloads

My first solution to this was to implement a "partial reload" system.

The way this works is that when a level is restarted, only the game objects are reloaded. The level's geometry, i.e., all of the tileset tiles, are kept from the last time the level loaded. This was a somewhat simple solution that easily cut the restart time in over half.

But there was still the initial load time issue. Nobody wants to wait 20 seconds for a level to load, even if the restart takes less than half that.

After a few experiments to find out what was causing levels to load so slowly, I discovered that a major bottleneck was just the amount of time it took the system to read the text files that the levels were stored in.

Removing unused junk from object data

These levels were created with a map editor called Tiled, and stored in the game as JSON files. By default, Tiled exports a lot of data about the objects and tiles in each level -- most of which Emerald Shores doesn't use. For example, the "rotation" property is completely unused, because none of the enemies/coins/items in Emerald Shores have a default rotation that can vary between instances. A quick experiment in manually removing all of those unused properties from a level concluded that it would decrease loading times by a noticeable amount.

My initial attempt to add this into my workflow was to write a custom exporter for Tiled, similar to the JSON exporter, but which would neglect to export the unused data. I ran into a few technical hurdles there when attempting to do this while keeping Tiled itself updated to its latest version, so I came up with another solution instead.

I used my experience in web development to write a command-line program in JavaScript, with Node.js. The program loads all of the level files, reads them, and then re-exports them as JSON again. Simple enough.

A program I wrote to "compress" level files by removing unused data

A program I wrote to "compress" level files by removing unused dataHowever, there was still room for even more improvement.

Removing empty tiles: the first attempt

Tiled exports data for every tile in the level -- even when a tile was empty. In other words, if a level was 30 tiles wide and 40 tiles high, there were 1,200 entries for tile data in the level file, even if the top half of the level is blank and only ground tiles exist. That made the level file significantly bigger, and, in turn, made it take longer for the game to load the level data from the file.

Every tile exists in the file in order, so the game knows that the first tile will be the top-left-most corner, and then the next tile will be immediately to the right of that, etc.

My first experiment here was to remove all empty tiles from the level data, and then add "x" and "y" coordinates for the tiles that did exist. This actually ended up making most level files larger, so I scrapped the idea. Oh well, it was worth a try. But the problem still needed a solution.

Removing empty tiles: the second attempt

It occurred to me that, in most levels, most of the empty tiles were in the top-left corner of level. What if I could get rid of those, and tell the level-loader that the first tile it sees in the level file isn't actually at position 0,0 (the top-left corner), but at something like 300,20 -- or whatever the first non-empty tile in that particular level ends up being.

So, that was what I did. I added onto my level-compression program a feature to remove all of the first tiles it comes across, until it finds one that's not empty. And then it would make a note of the coordinates of the non-empty tile, so that the level loader knew the coordinates of that first tile, since it could no longer assume that the first tile would be at position 0,0.

After I finished updating the level-loading code to be able to handle this newly-modified level format, loading times were reduced even further. At this point, most levels took fewer than 5 seconds to initially load, with the longest I timed being about 8 seconds. Much better than the 20-30 seconds. And with the "partial reload" system still in place on top of that, it only takes a couple of seconds to restart a level once you're already in it. Phew. Countless hours paid off.

Optimizing the framerate

There were two areas that seemed to cause the framerate to take a dive: particle effects and large backgrounds. Everything else seemed to have little to no impact on the framerate. So, naturally, these are the two areas where I took it upon myself to put in a bunch of Vita-specific checks in determining what the game should render versus what it should skip in order to make the game run faster.

Reducing particle effects

It was mostly the bomb particle effect that caused issues.

The solution here was pretty simple: I removed the explosion particle effect, and replaced it with a "Bomb!" action-comic-like image reminiscent of the bombs in Super Mario Bros. 2. If you're playing the game on PS Vita or PlayStation TV, you'll see that image when a bomb explodes; otherwise, you'll see the nicer-looking explosion particle effects.

Simplifying backgrounds

Large backgrounds seemed to take a toll on the framerate for whatever reason. I speculated that it was due to the game swapping textures in and out of memory, but GameMaker's debugging tools didn't help me much to confirm or deny that, and experimenting with the texture swap settings didn't help, either.

So I was going to need to just simplify the background images. Through trial-and-error, I discovered that if background images took up more than about half the screen space, the framerate would usually drop. In the first level of the game, this meant having clouds and mountains would cause a framerate drop, so I disabled the mountains. It's probably not something you'd notice unless you're actively looking for it, so it wasn't a huge deal; the mountains just add a little more immersion to the scene, but they aren't critical.

In some cases, such as level 1-2: Forest of Secrets, I was able to keep the backgrounds by simplifying them.

On the PS4 and PC versions of the game, the forest background is made up of three parallax images. In the PS Vita version, I've combined these into one smaller image that takes up half of the screen instead of the full screen. The parallax effect is gone, but otherwise the scene doesn't look terribly different.

1-2: Forest of Secrets on PS4

1-2: Forest of Secrets on PS4 1-2: Forest of Secrets on PS Vita

1-2: Forest of Secrets on PS VitaConclusion

Optimizing a game for older platforms is tough work, even for games that don't appear to be technically demanding. All of the optimization efforts I put into the game were for the Vita specifically; the game always ran smoothly on other platforms. But the Vita launch was always a priority, having started as a PlayStation Mobile project years ago, so I was determined to make sure it was playable.